Australia is a net exporter of grains, most of which will make its way out of the continent on bulk vessels. Grains are undifferentiated commodities with largely no difference between origins, therefore the cost of logistics becomes a primary driver of competitiveness. In this article we dive into the Baltic Dry Index and its impact on markets.

So what is the Baltic Dry Index (BDI)? The BDI is an index which tracks the cost of bulk shipping around the world. The index is calculated on a daily basis and covers twenty typical routes using three vessel types (Capesize, Panamax and Supramax.) This gives an indication of the trend in price movement, and provides an insight into how much it will cost to transport bulk commodities i.e. a lower BDI would indicate reduced freight costs.

This is important for Australian producers as we typically export the majority of our grain and oilseed production. A low freight rate therefore reduces the benefit of geographical advantage.

The BDI has a secondary function. It is considered by many to be a leading economic indicator. The cargoes typically transported by bulk vessels are commodities requiring further processing (iron ore, coal, grains etc) to create a product. This gives a potential indication of future economic growth, as the demand for raw commodities such as iron ore will increase as economies grow.

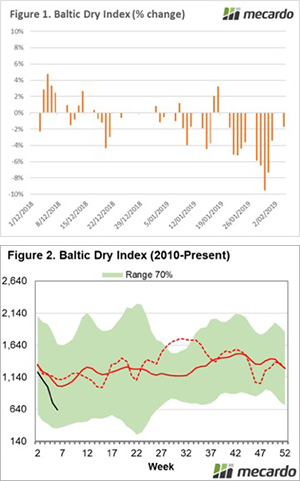

So why are we talking about it? The BDI has submerged (pardon the pun) in recent weeks. In figure 1, the daily change in the BDI is displayed since the start of December. The last positive move was on the 8th of January. This has resulted in a 50.5% fall in the index since the start of January.

It is not however wholly unexpected to see a fall in the BDI, as seasonal trends do tend to show a dip in the first two months of the year (figure 2). The index currently sits at 634, which is a low level albeit within the range which has been experienced during this decade.

So why has it fallen? There are several theories as to why the BDI has capsized, and a combination of all are likely to have had an impact:

- The Vale dam collapse in Brazil which has led to the loss of 134 lives has resulted in up to forty million tonnes of iron ore being removed from the market, as Vale decommissions similar facilities.

- The Chinese economy looks to be taking a turn for the worse with the Caixin manufacturing purchasing managers index falling below expectations signaling a deterioration in the manufacturing sector.

- Seasonal slow down ahead of the Chinese lunar new year.

- Continued overcapacity of bulk vessels and mismatches of vessel sizes.

What does it mean/next week?:

If the sharp decline in the BDI endures, this does not bode well for global economies – especially China. The Australian economy is heavily reliant upon China as a trading partner, and any fall in their buying power will have an impact on many of our commodities and food products.

The fall in the index along with poor economic data emerging in China may spur a quick resolution by the Chinese delegation in the Trump tariff talks.

The fall in the BDI does not mean that grain prices will fall, however it does mean that traditional trade flows become less important as shipping costs fall.

Key Points

- The BDI is an indicator of the cost of bulk shipping rates, but also holds a secondary function as a primary economic indicator.

- The BDI has keeled over, sinking to the depths of 634 from 1282 at the start of January.

- The sudden fall could point towards a coming slowdown in the global economy.

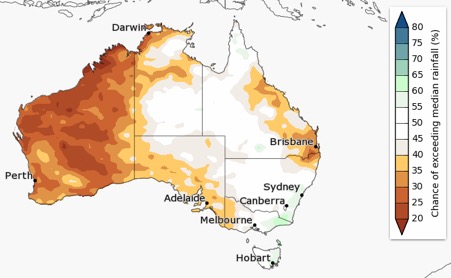

The bureau of meteorology has released its three month climate outlook. It doesn’t look good for Queensland and the West. After a fantastic year where WA produced a 17.5mmt crop, pre season rainfall has a limited chance of exceeding the median. This will put a dampener on expectations for the coming season. However, I have a few thoughts when it comes to this projection:

The bureau of meteorology has released its three month climate outlook. It doesn’t look good for Queensland and the West. After a fantastic year where WA produced a 17.5mmt crop, pre season rainfall has a limited chance of exceeding the median. This will put a dampener on expectations for the coming season. However, I have a few thoughts when it comes to this projection:

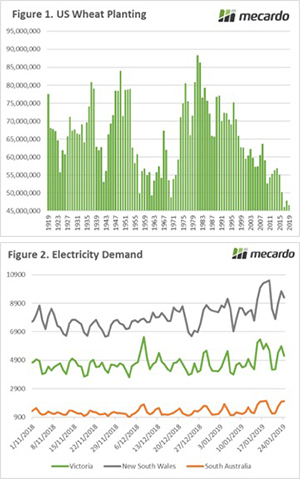

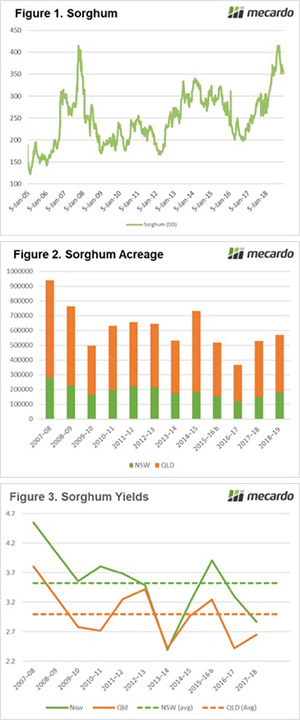

In lieu of data from the USDA, private forecasts become more important. Farm Futures in the US have conducted a survey of producers in order to gain an insight into planting expectations. It is anticipated that corn will rise by 1.3% year on year. There will however be major downward revisions to tariff impacted soybeans and sorghum with a substantial 5.5% and 12.1% reduction.

In lieu of data from the USDA, private forecasts become more important. Farm Futures in the US have conducted a survey of producers in order to gain an insight into planting expectations. It is anticipated that corn will rise by 1.3% year on year. There will however be major downward revisions to tariff impacted soybeans and sorghum with a substantial 5.5% and 12.1% reduction.

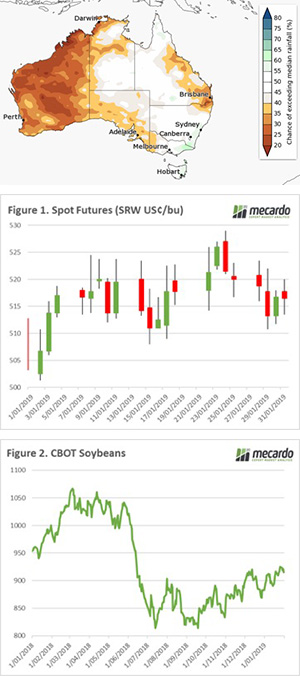

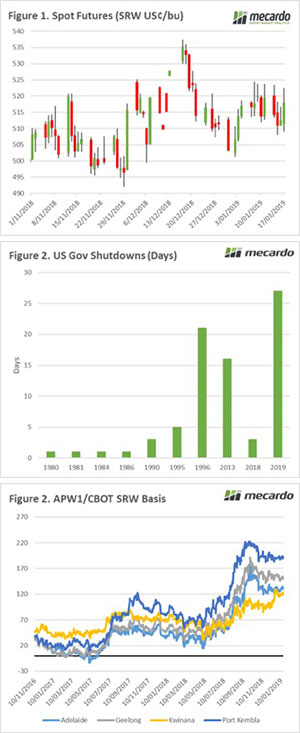

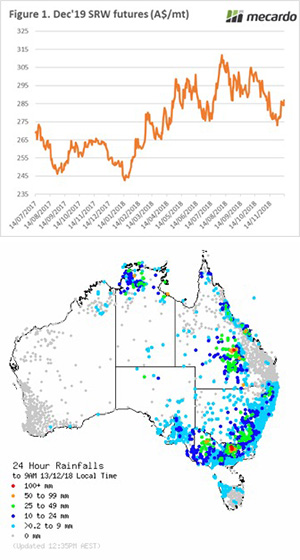

January is typically a quiet month for overseas markets. This month has been no exception to the rule. Chicago wheat futures are unchanged week on week in both US$ and A$ terms (Figure 1). The US will receive snow cover during the weekend, which will benefit the development of the crop. It provides protection against forecast cold snaps.

January is typically a quiet month for overseas markets. This month has been no exception to the rule. Chicago wheat futures are unchanged week on week in both US$ and A$ terms (Figure 1). The US will receive snow cover during the weekend, which will benefit the development of the crop. It provides protection against forecast cold snaps.

intensified. Since April 2018 the female slaughter ratio extended beyond levels experienced during the last significant reduction in the cattle herd, during the 2014/15 drought, and with an annual average female slaughter ratio for 2018 above 50% demonstrates that the herd liquidation remains well entrenched.

intensified. Since April 2018 the female slaughter ratio extended beyond levels experienced during the last significant reduction in the cattle herd, during the 2014/15 drought, and with an annual average female slaughter ratio for 2018 above 50% demonstrates that the herd liquidation remains well entrenched.

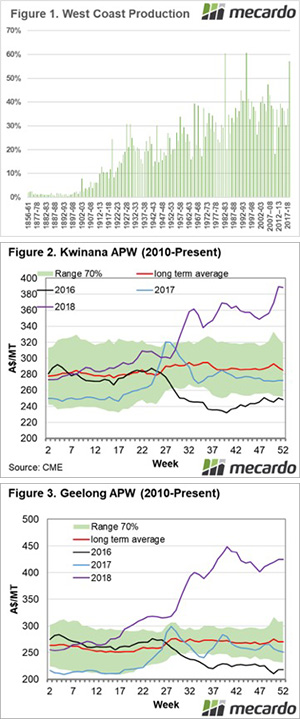

It is always important to look towards the horizon when creating a strategy for grain marketing. This is especially true this year, as producers in Australia are all likely to receive a historically high price due to the local drought conditions. There isn’t much strategy really required in a year like this.

It is always important to look towards the horizon when creating a strategy for grain marketing. This is especially true this year, as producers in Australia are all likely to receive a historically high price due to the local drought conditions. There isn’t much strategy really required in a year like this.

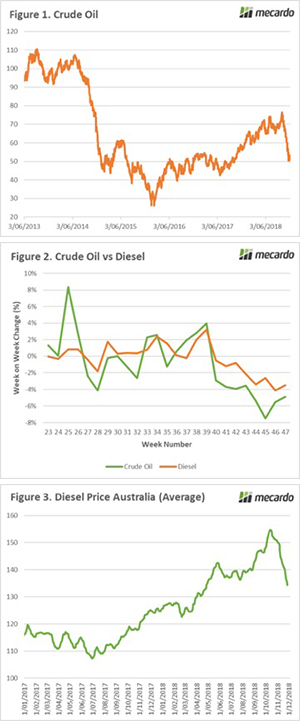

In mid-September, I covered fuel in the sarcastically titled ‘

In mid-September, I covered fuel in the sarcastically titled ‘