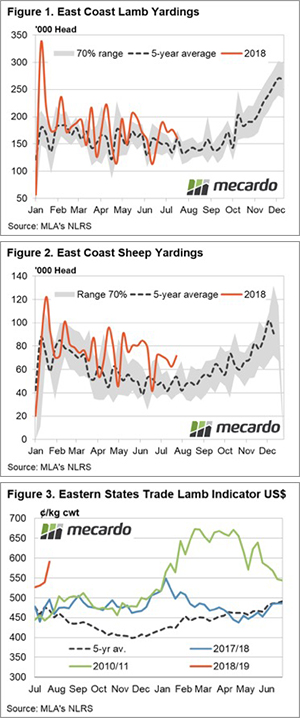

Price volatility, market uncertainty and climate variability across regions can play havoc with the normal seasonal spread behaviour between categories of sheep and lamb. With the Eastern States Trade Lamb Indicator (ESTLI) coming off record highs, the ongoing live sheep export issues facing WA producers and dry conditions affecting NSW producers we thought it time to assess the state of play with regards to state spread behaviour for a range of categories of lamb and sheep.

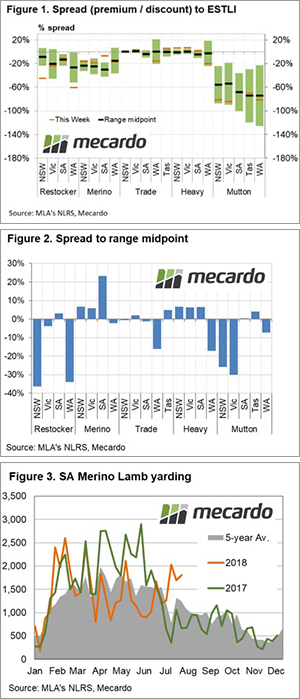

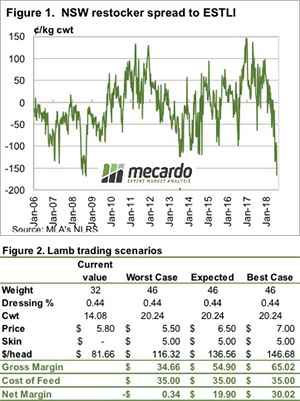

Analysis of percentage price spread discounts and premiums for a variety of categories of lamb and sheep across the states is shown in Figure 1. The orange dash signifies where the current price spread premium or discount is sitting relative to the ESTLI.

Overlaid on the chart is the historic mid-point for the spread, which gives an idea of the average seasonal spread level for this time in the year (black dash), and the normal seasonal range (green columns). The green columns show where the spread has fluctuated 70% of the time during this part of the season for the last decade.

The current discount spread for NSW Restocker Lamb shows that they are very much underpriced compared to the ESTLI with the spread level sitting well below the normal range at a discount of around 45% to the ESTLI. This is unsurprising, given the dry conditions facing producers in NSW now.

Interestingly, the WA Restocker Lamb spread shows a similar picture to the NSW situation, with the discount spread of around 60% to the ESTLI sitting below the normal seasonal range. The seasonal conditions in WA haven’t been as dire as those facing NSW producers but perhaps the uncertainty around the live export trade is giving WA producers second thoughts about building up flock size.

To get a quick snapshot of the categories of lamb and sheep that are significantly above or below the normal level we have produced a chart that shows the percentage that the current spread level is above or below the average midpoint level (Figure 2). Along with Restocker Lamb in NSW and WA it shows that WA Trade Lamb, WA Heavy Lamb and NSW/Victorian Mutton are all registering below par spread performance at the moment.

However, on a positive note, the South Eastern mainland states Merino and Heavy Lambs are faring relatively well, registering current spread levels that are 5-25% above the norm. The stellar performance of wool prices this season is underpinning Merino Lamb prices and is appearing to keep the Merino spreads to the ESTLI in good shape.

What does it mean/next week?:

The SA Merino Lamb spread is performing particularly well compared to the other state Merino classes. This seems to have drawn out a few more Merino lambs in SA in recent weeks with the yarding level trending around 45% above the seasonal average (Figure 3).

The additional supply of Merino lamb in the SA saleyards is likely to put pressure on the spread in the coming weeks to see it move back toward more normal seasonal levels.

Key points:

- WA lamb and sheep spreads to the ESTLI have been underperforming in recent weeks which suggests that the uncertainty around the live sheep export situation may be having an impact on price.

- NSW Restocker and mutton spreads showing the most impact from the dry conditions.

- Merino and Heavy Lamb spreads in the South Eastern mainland states are performing best, with SA Merino Lamb doing particularly well.

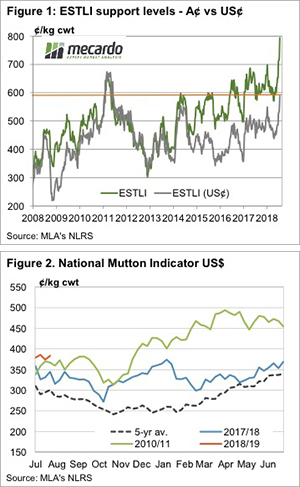

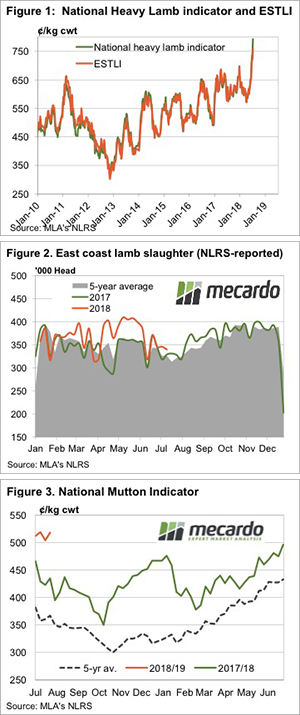

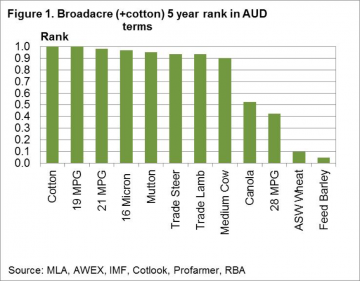

Figure 1 shows the January 2017 five year price rank for a range of broad acre (plus cotton) commodities grown in Australia. The price rank is looked at in Australian dollar terms, as farmers here in Australia see the prices.Basically the news is all good for livestock products (wool and meat) with the exception of crossbred wool (represented here by the 28 MPG). Five year price ranks are all in the top decile, meaning they have traded at lower levels for 90% of more of the past five years. Cotton also is trading in the top decile. At the other end of the scale lie canola, wheat and barley, with canola performing reasonably well by trading at median levels. Wheat and barley are in the bottom decile for the past five years.

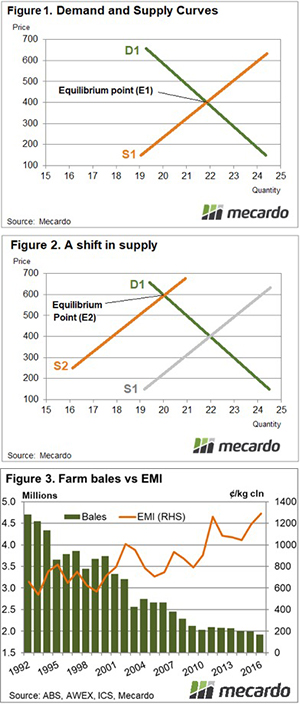

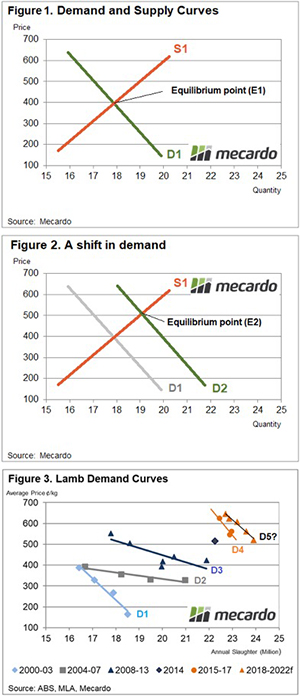

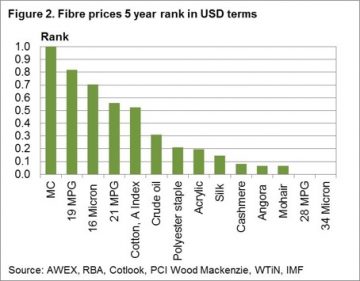

Figure 1 shows the January 2017 five year price rank for a range of broad acre (plus cotton) commodities grown in Australia. The price rank is looked at in Australian dollar terms, as farmers here in Australia see the prices.Basically the news is all good for livestock products (wool and meat) with the exception of crossbred wool (represented here by the 28 MPG). Five year price ranks are all in the top decile, meaning they have traded at lower levels for 90% of more of the past five years. Cotton also is trading in the top decile. At the other end of the scale lie canola, wheat and barley, with canola performing reasonably well by trading at median levels. Wheat and barley are in the bottom decile for the past five years. The next step is to look at these commodity prices from outside of Australia. In this case we use US dollar five year percentiles and break the commodities into groups. Figure 2 looks at fibres, including wool from Australia and a range of other apparel fibres. The price ranks range from a high top decile performance by the Merino Cardings indicator through to bottom decile performances by cashmere, angora, mohair and crossbred wool. The merino combing indicators perform well (ranging from the sixth to the ninth decile) well above oil and the synthetic fibres. Cotton comes in close to the 21 MPG in the sixth decile. The longer the disparity continues between the high merino rankings and lower rankings for the major fibres, the more likely some demand will shift out of merino (especially the broader side of 19 micron) to alternative fibres.

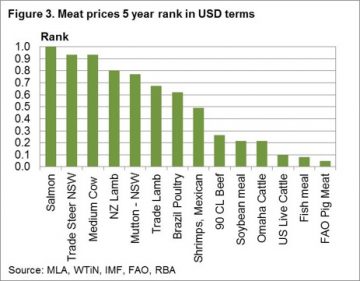

The next step is to look at these commodity prices from outside of Australia. In this case we use US dollar five year percentiles and break the commodities into groups. Figure 2 looks at fibres, including wool from Australia and a range of other apparel fibres. The price ranks range from a high top decile performance by the Merino Cardings indicator through to bottom decile performances by cashmere, angora, mohair and crossbred wool. The merino combing indicators perform well (ranging from the sixth to the ninth decile) well above oil and the synthetic fibres. Cotton comes in close to the 21 MPG in the sixth decile. The longer the disparity continues between the high merino rankings and lower rankings for the major fibres, the more likely some demand will shift out of merino (especially the broader side of 19 micron) to alternative fibres. Figure 3 looks at meat and protein prices from around the world. Salmon is the best performer followed by Australian beef and Australasian sheep meat prices. At the other end of the rankings are range of US beef quotes, along with fishmeal and the FAO pig meat index. The big discrepancy between Australian and US beef price ranks indicates some risk to Australian prices if US prices do not lift.

Figure 3 looks at meat and protein prices from around the world. Salmon is the best performer followed by Australian beef and Australasian sheep meat prices. At the other end of the rankings are range of US beef quotes, along with fishmeal and the FAO pig meat index. The big discrepancy between Australian and US beef price ranks indicates some risk to Australian prices if US prices do not lift.